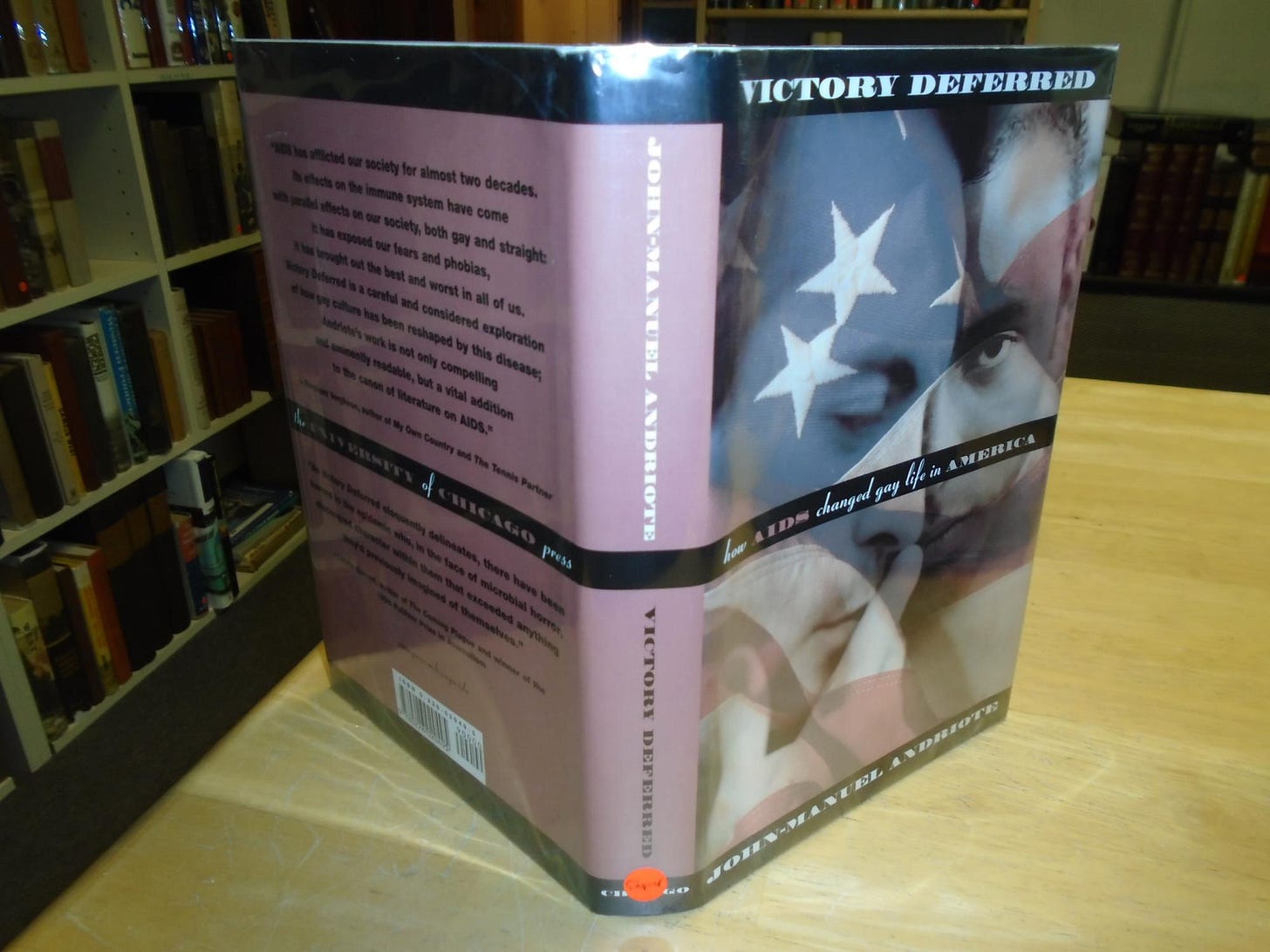

Review of “Victory Deferred: How AIDS Changed Gay Life in America,” by John-Manuel Andriote, 1999, University of Chicago Press, cloth, 421 pages.

A great deal of the solutions have come from gay men themselves.

This is a powerful and insightful classic which tells of yet another disenfranchised and marginalized group in society: gay men. The author does a great job in explaining the beginnings of the crisis and is very candid and straightforward about how various forces, including politicians, did a good job of helping AIDS spread not only throughout this country but also throughout the world.

Andriote gives readers an incredibly detailed explanation of what happened before, during and after the onslaught of AIDS in this country. Pulling no punches, he tells us of the ways the disease got a strong foothold early on, and how very little was done on a large enough scale to stop it from growing. We get the whole story here, starting from the very first days.

Andriote reminds us that Ronald Reagan’s contribution is very obvious.

Reagan did a very good job of allowing AIDS to flourish as he ignored the danger signs, ignored the messy topic, and tried to focus on events not involving gay men. By the time AIDS was killing straights and women and children, the crime had already been committed, for AIDS proved to be too strong a predator. The epidemic rushed forward.

That some people still vote for Republicans, still revere Reagan for any positive results of his presidency or still support the kinds of family values pushed by some of the more vocal GOP members is amazing to me. And rather frightening. I have been known to refer to that camp as the “Hatred Party.” Reading this book did nothing to mollify me in my disgust about how these people handle social conflict and needs.

Andriote reminds us, also, that Clinton was a disappointment because of his failed attempts to provide attention to the needs of gays and lesbians and others. Although he did openly address gay groups, and he was the first president to view the Quilt, Clinton waffled when it came to legislation to protect gays and reneged on his policy to condone gays in the military. Clinton was slow in doing what desperately needed to be done after the Reagan years.

Hesitation on the part of many elected officials let AIDS continue to grow, and gay men themselves were reluctant to radically alter their sexual practices in the first years of the epidemic because they did not know how the disease was caused or how it was spread. Certain social service organizations were reluctant to talk openly about some of their goals and programs, and some of the secrecy made it difficult for dollars to get where they needed to go, treatment to reach the most needy victims, and information that was crucial to reach as-of-yet non-infected individuals to impact positively on their lives. In short, great fear and lack of communication spread just as fast as AIDS.

The author tells us about in-fighting among various gay organizations in the country who had difficulty accepting their roles, and defining them, in the face of so much death and worry and grief of an entire people. That they fought and fell into some of the ugly conflicts they disliked in non-gay groups shows their weakness in the face of the threat of what would prove to be the slippery and demonic foe AIDS.

While there was a lack of cooperation on some fronts, the collaborative model of AIDS care established early on in San Francisco proved to be most beneficial.

In 1985, when the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation authorized over $17 million for an “AIDS Health Services Program,” the administrators invited Dr. Philip Lee from California to explain how the collaboration of social workers, doctors and community leaders could be achieved.

A great deal of the solutions have come from gay men themselves. Andriote reminds us of the volunteering and the donating and the other work done by gays because we did what we had to do, without having time to stop and ask “how.”

Although it is true AIDS has served to politicize gays and others in this country, the epidemic has also taken us backwards. It is true that the general public knows more about homosexuality now, but it is also true that they do not know enough. That we do not have comprehensive federal laws protecting gays and lesbians shows more work needs to be done.

That we do not have more effective medical treatment for AIDS patients is another sign that we need to move ahead and work even harder.

It is very difficult to read this book without becoming extremely angry. Those of us who have lost many of our best friends have difficulty being patient when people do not see the extreme need and the desperation brought on by the epidemic. Andriote reminds us of the ways some individuals and groups worked selflessly to try to fight AIDS—and how some people who had access to a huge amount of power, resources and personnel did little or nothing to fight it.

It is important to remember the past because it can teach us a great deal.