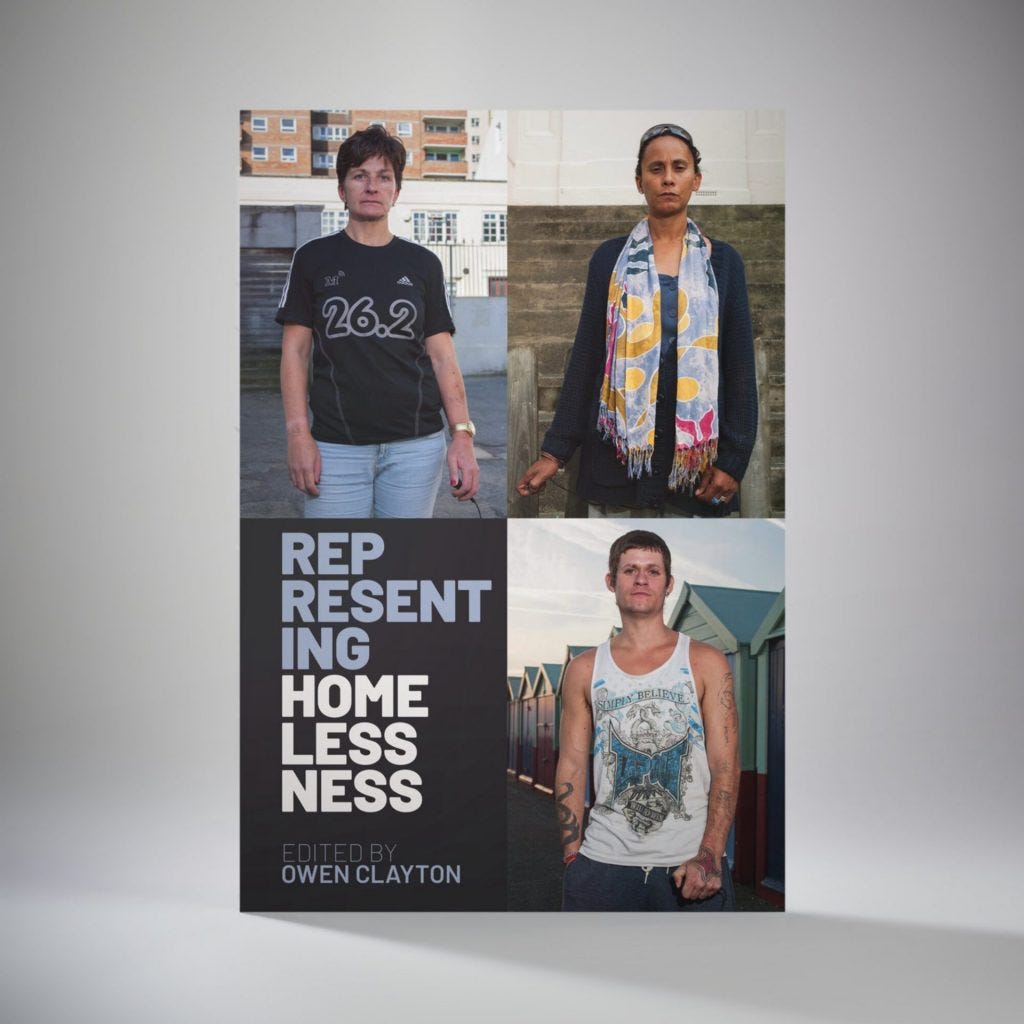

Review of book “Representing Homelessness,” edited by Owen Clayton, 2021. (Proceedings of the British Academy #239). London: Oxford University Press. Cloth, 218 pages.

I recommend this excellent book for use in courses and in professional development!

This is an excellent book for two major uses: 1) required reading for a course on understanding homelessness (social work, nonprofit management, sociology) and for 2) professional development for counselors and others helping the unhoused and attempting to get them housed.

One huge lack that is always clear to us working in the streets with unkeyed persons is that new graduates of college and university programs have little or no understanding of homeless people. Although they mean well, they just do not know what it is like to constantly be looking for food, showers, safety, respect, and clean drinking water. These kinds of needs are covered and considered the most basic elements of a new MSW’s life. How to communicate everything to these new professionals we need to get across to them?

This book does a great job of assembling notes from a conference on homelessness and adding up-to-date pieces on other aspects of the world of the unhoused. The readings are candid in both their support of the unkeyed persons living out there and also the importance of helping those individuals.

The very first reading attempts to explain why non-homeless people have misconceptions and hang-ups about the homeless. In effect, the authors explain what is wrong with people who fear, distrust, hate, and avoid the homeless. What weaknesses does the average person have? What shortcomings in dealing with and helping those in need?

Other readings go on to talk about laws and policies, and tendencies and realities of how the world deals with the unkeyed…

Again, most the readings deal with British settings and processes.

At the core of the book is the idea of “representation.” This has to do with the unhoused are presented to the world, how people see them, how people do not value them. Dehumanizing the homeless and disenfranchising them are typical and daily activities for people with money and power and keys to a place to live. The book is a candid explanation of what goes on out there.

There are 11 different readings, with most focusing on British policies and programs. There are a couple US readings also.

One reading, “The Power of One: The Media and Homeless Stereotypes,” by Paul Atherton, is very telling when it comes to how the unhoused probably act, certainly must behave, and why they cannot be trusted to get working, get rent paid, and get on with life. Being through foster care settings, being Black in England, and getting evicted several times as he struggled to find food and housing, are important parts of Atherton’s life that he wants to communicate. Not all the homeless are the same. Not all individuals have the same needs, fit the same patterns, or make poor decisions. He has learned to survive DESPITE the help people have forced him to accept.

An important aspect of the book is the inclusion of these pieces that consist of reports from the street, in fact, from the unhoused themselves. This use of tales coming from “lived experiences strengthens the book and makes it more complete.

All the talk of the homeless would be incomplete without the unhoused themselves weighing in to give their side of the story, the actual daily needs and struggles, in addition to dealing with the dehumanization at the hands of the wealthy (meaning people who have a place to live).

It is from these rich—and dehumanizing—experiences that a deeper understanding of life can come. The days of being homeless are important to communicate to young students and professionals, to the new MSW graduates who plan to make a difference out there.

The notion of “lived experience” has a strong tradition—and a growing one—in many areas such as substance abuse and other impactful training and education areas. Note how often it is heard that the best way to help someone who is having trouble shaking their drug habit is to get them in touch with a recovering drug addict? Drinkers who are in recovery are at the core of the philosophy of all 12-step programs also. They are “in recovery” rather than being considered “recovered” from alcoholism, for example. They keep recovering every day. They do not suddenly consider themselves “recovered.”

Having no background in substance abuse personally makes a counselor suspect, in many circles. Why would lack of experience living on the street, sleeping on the train, or years of standing on a corner and hoping for donations of cash or food be any different?

The second use for this book, professional development (PD) applications, is easy and clear also. In group sessions with persons (and volunteers too!) working in the streets there is a great deal of both general and specific information here…

I see great potential in this book as a PD device – namely a starting point for professionals and street helpers alike to read and then discuss over time. I would enjoy using the book that way myself, in PD and related sessions for those who help the unhoused.

In all, this is a great book for those learning how to become counselors and for those wanting to enrich and deepen their understanding of persons out there who are unkeyed individuals.

I recommend the book and hope my review will inspire some professionals and street helpers alike to read it and study it. I myself would enjoy using the book in topics courses and PD sessions.