Higher Cancer Incidence Reported Among the Homeless: Data from Studies

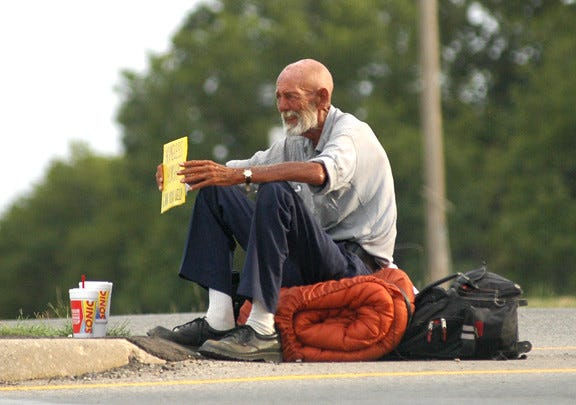

The data is clear: If you are homeless, especially if you are a homeless senior, there is an increased chance you will contract cancer and die from it

How do we know that persons living outdoors or on the train or in a shelter stand a greater chance of having certain types of cancer than their indoor neighbors? Why do homeless people become ill? What can we do to intervene and resolve the problem? How do we get them healthcare and health insurance?

The majority of chronic and longer-term homeless situations create a situation in which the unhoused individuals do not have health insurance, do not seek healthcare, and do not report the “right kinds” of warning signs to social workers, counselors, and street helpers. The unkeyed are not communicating that they might have cancer or that they have aches and pains that could be a sign of that. They give little information on these topics to the persons trying so hard to help them. Those professionals and grassroots helpers have to “read between the lines” to detect what could be cancer or other serious illnesses.

A recent study (covering the years 1999 to 2019) revealed that living in a homeless condition indeed increases one’s chances of contracting cancer. Coupled with poor dietary choices, lack of healthcare, and lack of impetus to report cancer-like symptoms, the unhoused are presenting with cancer—and on an increasing basis. There are in fact great disparities between the cancer rate for housed vs. unhoused persons. In other words, if you are homeless, you stand a great chance of (already) having cancer. The report warns, “These findings provide clinically relevant information to understand the cancer burden in this medically underserved population and suggest an urgent need to develop cancer prevention and intervention programs to reduce disparities and improve the health of homeless persons.” (“The Epidemiology of Cancer Among Homeless Adults in Metropolitan Detroit,” by Andreana Holowatyj, et al., JNCI Cancer Spectrum, reported by the National Library of Medicine online, 2019 Mar 25;3(1):pkz006, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6433093/).

The above information is of great concern to those who help younger homeless persons, of course. Coupled with the higher risk of cancer among young people is the fact that a great percentage of the unhoused identify as younger members of the LGBTQ+ communities. Note that a recent study reveals, “The declining health status of Americans, particularly among younger individuals without pre-existing conditions, together with projected cancer incidence and mortality rates, underscores concern about worsening acuity and cancer incidence.” (“Longitudinal Analysis of Patients Receiving Treatment for the Most Common Cancers Reveals Increases for Several Types,” by Sanjula Jain, The Compass, Trident Health, July 14, 2024, https://www.trillianthealth.com/market-research/studies/patient-treatment-analysis-uptick-common-cancers?utm_source=bing&utm_medium=ppc&utm_campaign=Service%20Line%20Intelligence&utm_content=oncology&utm_term=oncology%20incidence&hsa_acc=1966436256&hsa_grp=1312819300983296&hsa_ad=&hsa_src=o&hsa_tgt=kwd-82052379035429:loc-190&hsa_kw=oncology%20incidence&hsa_mt=p&hsa_net=bing&hsa_ver=3&msclkid=51474e728ab21f88d5a129f5710c240f ).

We know also that older unhoused persons, especially, stand a higher risk of dying early than their indoors neighbors and relatives. We also know through studies that the older one becomes homeless, the greater the chance that person will die early. A recent article reports on the status of homeless seniors and produces some results on all of these factors. The results are not encouraging, to say the least. The study which was funded by the National Institute on Aging, recruited people who were 50 and older and homeless, and followed them for a median of 4.5 years. The researchers interviewed the subjects every six months. “They found that people who first became homeless at age 50 or later were about 60 percent more likely to die than those who had become homeless earlier in life.” Further, the researchers discovered that “those who remained homeless were about 80 percent more likely to die than those who were able to return to housing.” And the main causes of death among homeless seniors are known also: “Our investigation of the burden of cancer among individuals who were experiencing homelessness, as compared with nonhomeless, at diagnosis of first primary invasive cancer in metropolitan Detroit revealed that proportions of cancers of the respiratory system, in particular malignancies of the lung and bronchus, were statistically significantly higher among homeless men when compared with the referent adult population of men diagnosed with cancer.” Among homeless women, in comparison with women living indoors, these results came through: “Statistically significantly higher proportions of female genital system cancers, particularly cancers of the cervix uteri and ovary, were observed among homeless women.” Overall, the cancer revealed that cancer diagnosed later is deadly among the homeless: “Together, homeless cancer patients exhibited statistically significantly poorer overall and cancer-reported survival when compared with a propensity score matched referent group.” The author of the article reporting on the study tells us that the “untimely deaths highlight the critical need to prevent older adults from becoming homeless – and of intervening and rehousing those that do” (“Older Homeless People Are at Great Risk of Dying,” University of California-San Francisco, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, UCSF Epibiostat news online, by Laura Kurtzman, August 22, 2022, thttps://epibiostat.ucsf.edu/news/older-homeless-people-are-great-risk-dying).

Yet another study looked at a population of unhoused persons and found a high incidence of later-reported cancers due to smoking. Experts in Boston at a well-known center studying homeless health studied various angles of cancer among this population. The researchers “…cross-linked a cohort of 28,033 adults seen at Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program in 2003–2008 to Massachusetts cancer registry and vital registry records.” They also “examined tobacco use among incident cases and estimated smoking-attributable fractions.” It turns out that the cohort of homeless adults had a high burden of tobacco-related cancer and was diagnosed with screen-detectable malignancies at a later stage than Massachusetts residents. It is predictable what that team of researchers recommended as one remedy of the problem of smoking-related cancers: “Prevention efforts should focus on reducing tobacco use and enhancing completion of cancer screening.” (“Disparities in Cancer Incidence, Stage, and Mortality at Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program,” by Travis P. Baggett, et al., American Journal of Preventive Medicine, reported by the National Library of Medicine online, November 1, 2016, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4615271/).

There are the facts.

Homelessness is expensive. Somebody has to handle the healthcare and counseling costs of people NOT living indoors in a usual dwelling.

Homelessness is deadly. Especially for older people without a place to live, illnesses and lack of healthcare will kill them. Living in a congregate situation such as a shelter is of little help longer-term: being housed closely with other people who have a variety of infectious and non-infectious diseases can be a death sentence. Smoking adds another dangerous element to the health and well-being of the unhoused.

What is the answer? Maybe there are many answers. Maybe most of them have to do with securing healthcare, and health insurance, for the unkeyed immediately.

Strategies such as “housing first” and others in which the unkeyed person is moved indoors, given towels and soap and food and furniture so that they can begin to recover from—and survive—having lived outdoors or in a shelter for some amount of time are needed. Quitting smoking is another important move toward gaining better health.

We know these strategies work. We know more people need to learn about them and support them. Housing, coupled with addiction counseling, smoking cessation, and the means for learning how to cope with the duties of maintaining an apartment, are all important pieces of the puzzle.

Easily solved. Or so it might seem.

.

.

For further reading, please see:

Decker, H., et al., (2024, February), “Housing Status Changes Are Associated With Cancer Outcomes Among US Veterans,” Health Affairs (43:2), https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2023.01003

Drescher, N., & Oladeru, T., (December 22, 2022). “Cancer Screening, Treatment, and Outcomes in Persons Experiencing Homelessness: Shifting the Lens to an Understudied Population,” Journal of Clinical Oncology online (19:3), https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/OP.22.00720

Levy, J. S., (2012). Homeless Outreach and Housing First. Ann Arbor, MI: Loving Healing Press.

Levy, J. S., (2011, July). “The Case for Housing First: Moral, Fiscal, and Quality of Life Reasons for Ending Chronic Homelessness. Recovering the Self: A Journal of Hope and Healing, III(3), pp. 45-51.

Tsemberis, S., Gulcur, L., and Nakae, M. (2004). "Housing First, Consumer Choice, and Harm Reduction for Homeless Individuals with a Dual Diagnosis". American Journal of Public Health. 94 (4): 651–56.